I am sadly not surprised by the disturbing reality of what Tina Lia of Hawai‘i Unites describes in her most recent article which I am reposting below.

Stealing Water: Disaster Capitalism on Maui

by Tina Lia – Founder, Hawai‘i Unites

HAWAII UNITES • 24 August 2023

Ola i ka wai

Water is lifeThe world is watching as an unimaginable tragedy continues to unfold in our small island community. The fires that devastated historic Lahaina town on Maui were an unprecedented failure of multiple agencies responsible for protecting the safety of the people. While we’re hearing increasingly disturbing eyewitness accounts from survivors, our government is withholding information and forbidding access to the entire area where the destruction occurred. The number of fatalities is being slowly released in a day-by-day tally that comes nowhere close to the true count of the tragic loss of lives here.

State controlled media is presenting a tale of bumbling decision-makers, crumbling infrastructure, poor communications, and bad planning. With just about every agency you can think of involved in this colossal dereliction of duties, this catastrophic event is starting to look more and more like the work of an organized crime syndicate. The question we have to ask now is who really made the final decisions, and why. I think we need to start with the water.

Hawaii Unites is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Disaster capitalism is a term used to define the practice of government and industry taking financial advantage of natural or man-made disasters, adopting unpopular policies and intervening in reconstruction and recovery efforts. Here on Maui, we already have a governor talking about the state taking over the land in Lahaina with plans to “build it back better.”

“I’m already thinking about ways for the state to acquire that land so we can put it into workforce housing, to put it back into families, or to make it open spaces in perpetuity as a memorial to people who were lost.”

“We don’t want this to become a clear space where then, yes, people from overseas just come and decide they’re going to take it. The state will take it and preserve it first.”

Joe Biden even got in on the action during his visit to Maui’s ground zero this week, promising a crowd of survivors:

“We’re gonna build back better. Better than you had. But what YOU want. What YOU need.”

Conveniently, governor Josh Green signed an executive order in the short weeks prior to the fire allowing him to fast track just that kind of action. Invoking an overreaching state statute that gives the governor (and mayors) broad power to suspend laws impeding emergency response in events such as natural disasters, on July 17, 2023, the “Emergency Proclamation Relating to Housing” was put into place. Concerns raised by the community about the order include the potential for exploitation of land and the environmental risks of imbalanced development taking precedence over protection of the ‘āina (the land and all its resources). The protective laws being suspended include provisions related to historic preservation and county and state zoning. The proclamation also suspends Hawai‘i ’s environmental review law, the Hawai‘i Environmental Policy Act (HEPA) process that requires comprehensive environmental impact statements for projects that are determined to have significant impact on natural and cultural resources. Hawai‘i ’s Sunshine Law requiring government transparency and the opening of decision-making meetings to the public has also been suspended.

No fast-tracked development would be complete without water infrastructure, and that appears to be a clear motive for this potential crime in progress. Some background can be found in this month’s article in The Guardian describing the efforts of one brave attorney to protect the water rights of West Maui’s Native Hawaiians:

“All over Maui, golf courses glisten emerald green, hotels manage to fill their pools and corporations stockpile water to sell to luxury estates. And yet, when it came time to fight the fires, some hoses ran dry. Why?

The reason is the long-running battle over west Maui’s most precious natural resource: water. That’s why, on Tuesday 8 August, when Tereariʻi Chandler-ʻĪao was fleeing the fires in Lahaina, she grabbed a bag of clothes, some food – and something a little unconventional: a box filled with water use permit applications.

Despite her personal calamity, Tereariʻi, a grassroots attorney, already knew that the fight for Maui’s future was about to intensify, and at its heart would not be fire, but another element entirely: water. Specifically, the water rights of Native Hawaiians, rights that a long parade of plantations, real estate developers, and luxury resorts have been stifling for nearly two centuries. As the flames approached, Tereariʻi feared that, under cover of emergency, those large players might finally get their chance to grab west Maui’s water for good.

She also knew something else: that the only force with a hope of stopping that theft would be organized grassroots communities – even though those very communities were already stretched to breaking point saving lives and searching for lost loved ones.”

The article goes on to explain the history of water rights in the area and the key corporate players involved. A recent victory for Native Hawaiians now hangs in the balance, as Green’s emergency proclamation is set to override the landmark decision that would have allowed the community access to their own natural resources:

“Which brings us back to what was in that box that Tereariʻi rescued, and the place of water in this fateful moment. For over a century, water across Maui Komohana, the western region of the island, has been extracted to benefit outside interests: first large sugar plantations and, more recently, their corporate successors. The companies – including West Maui Land Co (WML) and its subsidiaries, as well as Kaanapali Land Management and Maui Land & Pineapple Inc – have devoured the island’s natural resources to develop McMansions, colonial-style subdivisions, luxury resorts and golf courses where cane and pineapple once grew.”

“Together, the communities have been fighting for their right to manage their own water rather than watch as it is diverted for often frivolous uses. June 2022 saw a historic victory: heeding the overwhelming demands of Native Hawaiians and other residents, the water commission voted unanimously to designate west Maui as a surface and groundwater management area. Under Hawai‘i ’s water code, this designation invokes the commission’s permitting authority to protect priority Native Hawaiian rights and the environment over the historical and ongoing overexploitation of water by plantations and developers.

After protracted struggle, and despite predictable opposition from industry, the community and the water commission prevailed, instituting a new permitting system that the community hoped would restore public control over water that had been stolen for over a century. The Palakiko family and others began filling out water use permit applications requesting water for their household needs, like bathing their babies, and also water for Indigenous wetland agriculture.

But here’s the cruelest irony: the deadline to submit those permit applications to the water commission was on Monday 7 August. And the fire that devoured Lahaina was the very next day.”

Yes, you read that right. The water permit applications were due just one day before a “hurricane” of fire completely destroyed the entire West Maui historic capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom, a prime real estate area on the island. To borrow a phrase used recently by Josh Green himself, “I’ll leave that to you to explore.”

Green’s media statements appear to encourage an honest discussion about conflicts regarding the release of water to fight fires, though his comments have been curiously inflammatory. Maui’s water infrastructure is now under heavy scrutiny, and the situation surrounding accessibility of water during the Lahaina fire looks to be at the forefront of the recovery and rebuild strategy.

What we know at this point is that the water started running dry as firefighters were attempting to control the blaze. That system failure has been attributed to a combination of factors. The New York Times reports:

“Early that day, as winds knocked out power to thousands of people, county officials urged people to conserve water, saying that ‘power outages are impacting the ability to pump water.’

John Stufflebean, the county’s director of water supply, said backup generators allowed the system to maintain sufficient overall supply throughout the fire. But he said that as the fire began moving down the hillside, turning homes into rubble, many properties were damaged so badly that water was spewing out of their melting pipes, depressurizing the network that also supplies the hydrants.

‘The water was leaking out of the system,’ he said.”

The article further details how decision-making around the fire was made complicated by the connection between water and power:

“West Maui’s water system relies on electrical power to pump water through the network and deliver it to fire hydrants, and officials at Hawaiian Electric, the state’s main electrical utility, have said that the need to maintain this pumping capability has made it difficult to shut off power when high winds pose a fire risk.”

Meanwhile, local and national media outlets quickly jumped to throw Hawai‘i ’s Deputy Director of the Commission on Water Resource Management, Native Hawaiian cultural practitioner M. Kaleo Manuel, under the bus in what seems to be a coordinated effort to push the narrative that protection of indigenous water rights caused hydrants to run dry. The story is that on the day of the fire, West Maui Land Co. requested the release of water to help prevent the fire’s spread to properties managed by the company. Manuel delayed the requested diversion of stream waters to reservoirs for five hours, insisting that West Maui Land Co. get permission from a downstream kalo (taro) farm. By the time the release was finally approved, it was too late.

According to sources, though, the Kaua‘ula Stream that supplies the water isn’t actually connected to fire hydrants in Lahaina town. The water does, however, connect to the hydrants in West Maui Land Co.’s subdivision of gentlemen’s estates. If the fire had spread there, then those homeowners could have potentially protected their homes with the non-potable water that was flowing out of the reservoir and into their irrigation systems. Fortunately for those homeowners, the fire stopped just below their subdivision.

Community members are speaking out in support of Manuel, including West Maui kalo farmer Lauren Palakiko:

“The water here never touches Lahaina, Lahaina Town. Our water is diverted for the Launiupoko homeowners, which is agricultural-zoned gentlemen estates. So these guys take massive amounts of water for their pools and their water features, like their fountains and what not.”

“For your unbiased attention to underheard kanaka to the underdogs that have been getting trampled for decades now, really centuries. You know, we’re gonna keep staying here standing up, telling the truth.”

The fire department confirmed that high winds grounded air crews, preventing water from being scooped from the reservoirs. Confirmation was also made that Lahaina firefighters wouldn’t have had access through hydrants, since that water supply doesn’t feed into the county system.

Nevertheless, the Department of Land and Natural Resources that employs M. Kaleo Manuel has allowed him to take the heat for a decision that seems to have had no effect on the outcome of events on the day of the fire. In the days following, we learned that the DLNR had re-deployed Manuel to an undisclosed division of the agency. Longtime staffer Dean Uyeno has been temporarily assigned as interim Water Deputy.

Many in the community continue to defend Manuel, calling for him to be reinstated. This week, we learned that Maui residents Kekai Keahi and Jennifer Kamahoi Mather filed a lawsuit against Dawn Chang, chair of the Board of Land and Natural Resources and the Commission on Water Resource Management. The complaint alleges that Chang violated the Sunshine Law open meetings statute by re-deploying M. Kaleo Manuel without giving the people an opportunity to testify. The Plaintiffs are asking that the court void Manuel’s transfer.

While that story dominates national headlines, the governor is taking advantage of the distraction and has already started flexing his new emergency powers to take back control of water in the area. Water rights expert Dr. Jonathan Likeke Scheuer has suggested that the Manuel controversy is being used as an excuse to further a pre-existing agenda:

“[Green] suspended the water code in Lahaina due to the fires. He’s suspended certain other provisions of law in the housing proclamation. And in his comments on Monday, he specifically alleged something that I’ve never heard to be the case: that people are fighting against the provision of water for firefighting across Hawaii.”

The full extent of this Maui disaster hasn’t even begun to come to light. While a people’s inquiry is now underway to determine the facts of the Lahaina emergency response failure, rest assured that Josh Green and his cohorts already have a long-planned solution in the works. What better way to address the state’s neglected infrastructure, propensity for human error in all areas of decision-making, and lack of communication between critical agencies involved than to turn the entire production over to artificial intelligence (AI). What a coincidence that next month’s Hawaii Digital Government Summit plans to address just that. Summit sponsors Google for Government to the rescue! Google cloud systems for state and local governments provide AI, safety and traffic analytics, public health decision support tools, and more. Summit sessions such as “Digital Transformation for Government: The Future is Now,” focused on networking physical objects embedded with sensors, software, and other technologies through the Internet of Things (IoT) in connection with AI, will surely present high tech problem solutions for this unanticipated breakdown of Maui’s disaster response operations.

Stay tuned, and pay particularly close attention to the topic of water resources.

Hawai‘i Unites has taken the state to court to challenge their multi-agency project to release billions of lab-infected mosquitoes on 64,666 acres of East Maui’s natural reserve, watershed, and conservation area. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to our organization to help move our legal case forward.

Mahalo,

Tina Lia

Founder

Hawai‘i Unites

HawaiiUnites.org

Please share Tina Lia’s original post:

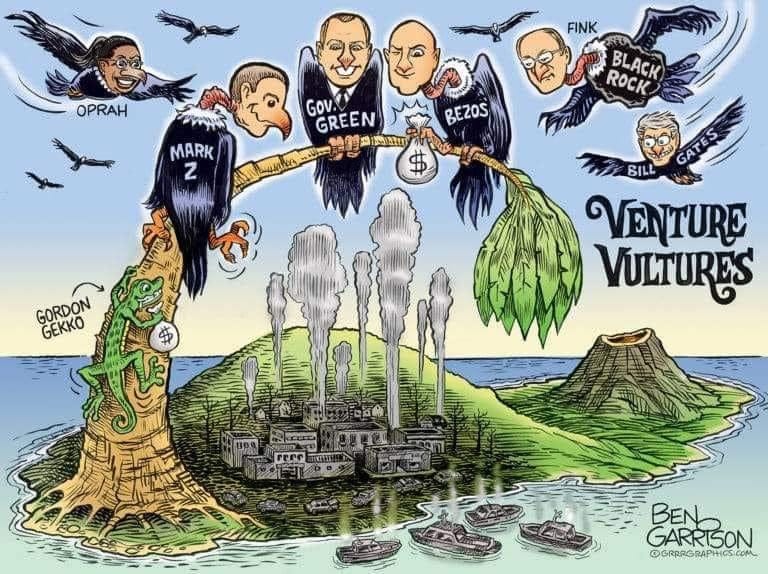

Someone shared this very appropriate image on social media:

It's another pre-planned take over.